Migrating Firefox for iOS to Swift 3.0

A week ago we completed the migration of the entire Firefox for iOS project from Swift 2.3 to Swift 3.0. With over 206,000 lines of code, migrating a project of this size is no small feat. Xcode’s built in conversion tool is a fantastic help, but leaves your codebase in a completely uncompilable state that takes a good long while to resolve.

When we migrated Firefox for iOS over to Swift 2.0 from Swift 1.0, a single engineer took on the task and the process took weeks. Even once the project had been brought to compilable state, it took several engineers a further week to ensure that all the tests passed successfully. We made a further mistake then by continuing to commit to master during the migration process. Seeing as this happened before we had released V1 of the app, the codebase was undergoing a large amount of daily change and resolving the merge conflicts between the migration branch and master caused no small amount of swearing over IRC.

It was this massive undertaking, and the knowledge of the amount of lost engineer time for developing new features, that kept us delaying the move to Swift 3.0. We knew it was essential, and that delaying was costing us, but there was just so much to do. Over the summer, one of our interns had started a branch for the migration, but the project was incomplete by the time his internship ended and it was left to stagnate.

We realised at the beginning of January that we just couldn’t hold off any longer. Xcode 8.2.1 was the last version that would support Swift 2.3 and if we didn’t move soon we would be restricted to using an older version of Xcode. When you are producing an open source project with many community contributors, that kind of restriction would cause all sorts of problems, not to mention the risk of our contributors abandoning our project for being out of touch. There were simply no more excuses.

We were determined not to make the same mistakes again. This time we came up with a plan. We revisited the Swift 3 branch that had been started the previous summer and evaluated whether or not it was worth using this as a starting point. We considered rebasing the changes over the latest code, but too much had changed in the proceeding months and it was decided that we were better off starting from scratch.

Our plan was simple. Move target by target, migrating each one by itself and ensuring the tests passed before moving on to the next target. All of our targets have their own separate schemes for building and this allows us to compile each in isolation of targets that are not dependent on them. In this manner we could have confidence in the accuracy of each target migration before we started working on those targets that depended on it.

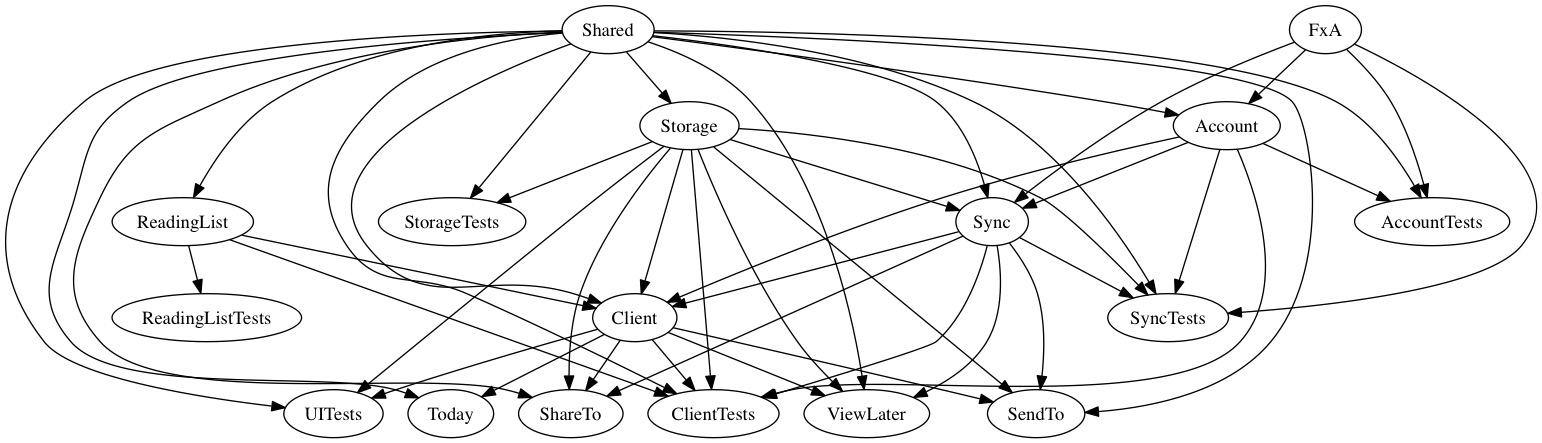

First, however, we needed to have a clear understanding of the dependencies between our targets and between those targets and our third party code. We needed to know in which order we should start to migrate. We used a tool called Graphviz to create dependency graphs that enabled us to visualise the dependency tree and also allowed us to identify which targets could be migrated in parallel and which had to be done sequentially.

From these we came up with the following migration path.

- Deferred

- Shared, FxA

- ReadingList, Storage, Account, Today

- ViewLater, ShareTo, SendTo, Sync

- Client

- UITests

In addition, we took a good hard look at our third party dependencies. We identified which versions we would need to upgrade to for Swift 3.0 support, and also what the impact would be when we started moving from much older versions of those frameworks. The largest changes occurred in Alamofire and Snapkit and we had to be aware that potentially significant changes would be needed in order to use these updated frameworks.

Once we had an idea in what order we should start to migrate, we created a number of bugs in bugzilla, each grouped under a metabug and each labelled with its dependencies so it would be easy to see which should be tackled in which order. Then we just had to schedule the work in.

We were helped with scheduling with the release of the first Xcode 8.3 beta at that time. Suddenly a version of Xcode without Swift 2.3 support was imminent and we knew we had to do the work sooner rather than later. However, we were coming up to our next version release, V7.0, and we knew the time spent on the migration would necessarily limit the scope of that release.

There were two arguments here. The first argued that the migration was a significant change, even if it doesn’t add any new features, and a risky change at that. Releasing a version of Firefox that only contained the migration would make it far easier to identify any regressions that were caused specifically by the migration. The second argument was that we had a number of features ready to go that were originally intended for this release and that holding off on the release of these features would significantly impact our release plans for future releases.

In the end we reached a compromise. We evaluated the features that were slated for the 7.0 release and identified the least risky and impactful and agreed to include those. Any features that we were uncertain of were bumped to a future release. This way we had a higher chance of identifying migration related regressions, while still providing added value to our users. We scheduled the migration to start at the beginning of the next sprint, with an estimate that with 3 engineers working full time it should take us about a week. We sent an email out to all of our contributors alerting them to the impending change and informing them of the merge freeze on master that would be in place for the duration of the migration.

With nothing left to prepare, we created a branch for the migration, created a slack channel for discussing migration related topics, declared the start of the merge freeze and got down to work.

The first hitch in the plan occurred fairly quickly. Our test targets, despite not importing code from other targets further down the dependency tree, all required our primary target, Client, as the host app in order to run. Therefore our plan to ensure each target robustly passed its tests before moving onto the next target was impossible. We would have to migrate all of the targets, then the test targets and then ensure that the tests pass. This would mean that we may possibly be performing code changes in dependent targets on incorrectly migrated code, which added an extra layer of uncertainty. In addition, being unable to execute the code before moving on would mean that if we made a poor decision when solving a migration issue, that decision may end up proliferating through many targets before we realised that the code change produces a crash.

The second hitch came when migrating some of the larger targets, in particular Storage. Even after all this time, Xcode’s ability to successfully compile Swift is…flaky. When, after performing the auto-conversion, your first build error is a segfault in Xcode, this is not at all helpful. Especially when the line of code mentioned in the segfault stack trace is in an unassuming class that is doing nothing special. And when you comment out all of the code in that class, it still produces a segfault. We had to employ some creative thinking to discover the causes. Attempting to compile using the Xcode 8.3 beta helped - this version seemed to give far more detailed information about the cause of the segfaults and really helped us narrow things down.

It quickly because obvious that we were going to be unable to parallelise the migration of targets with the level of efficiency that we had planned for. Some targets were simply taking too long to resolve all of the compilation errors and required code changes. With 3 engineers in 3 different time zones, this could have led to a lot of hanging around, waiting to be unblocked.

Fortunately for us, this was one of those rare situations in which timezones became an advantage. We stopped trying to parallelise and started to more efficiently serialise.

Our UK based engineer would work on the target until the end of her day. Then our Toronto based engineer would pick up where she left off and continue working until the end of his day. Then, our Vancouver based engineer would pick up what was left, continue and then hand over via Slack so our UK based engineer could pick it up when she came in.

In this way we were successfully able to continuously work on the migration and not be blocked on a single engineer. Crossover periods when all engineers were working together were used to tackle the trickiest of migration problems where multiple heads could brought together to hammer out a solution. It also helped share the knowledge of resolving migration issues between the engineers so we were able to bring consistency to our migration.

We used Slack extensively throughout this period. When an engineer resolved a problem or found a useful resource, that would be added to the Slack channel and pinned to enable other team members to quickly find it. When handing over work between timezones, we would add status reports that made it easy to pick up where the last engineer left off. Github integration meant that the entire team was kept abreast of progress as they could see when pull requests were raised and help review then, or simply keep track of which targets had been migrated if they wanted to chip in and help. It was also used to discuss our progress, formulate strategies and assign tasks. Doing this inside a dedicated space, outside of our usual irc channel ensured that no information was lost in chatter and everyone knew what was happening.

Due to these issues we quickly realised that a 1 week migration time was a severe underestimate. We ended up taking an entire 2 week sprint to perform the migration, then spent another 1.5 weeks in thorough regression testing and bug fixing. During this time we found some interesting nuances in the migration changes that were responsible for a number of introduced crash bugs. These included incompatibilities between implementations on NSKeyedArchiver which meant you needed different strategies for decoding objects encoded using Swift 2.3 than those encoded using Swift 3. And using Range(withUncheckedBounds: (lower: Bound, upper: Bound)) often resulted in the incorrect range and that we needed to use the shorthand lower…upper instead, especially when callingData.subdata.

Finally we had a branch running Swift 3.0 where all tests passed and our QA team was happy that there were no regressions. It had taken 3.5 engineers, 3 members of QA and 3.5 weeks, but the feeling when we were finally ready to hit merge was jubilant. But we couldn’t hit merge just yet. First, we had to contact all of the contributors who had outstanding PR’s to let them know that they would need to update their PR’s and re-submit once the migration had landed. Once that was done, we announced to the mailing list that the migration was landing, pressed the merge button and distributed virtual high-fives all around.

Here is a list of resources that we found useful during the migration:

- Working with JSON in Swift

- Naming Things in Swift

- Swift 3.0 Migration Guide

- Unsafe Raw Pointer Migration

- Handing Unused Result Warnings in Swift 3

- NSKeyed Archiver Nuances

This is a list of the causes of the compiler Segfaults we encountered.

- Using

AnyObjectto contain a JSON dictionary. Moving to using[String: Any]resolved this - Casting to

NSStringfromStringin order to call a function defined as anNSStringextension. ExtendingStringinstead ofNSStringresolved this - Using

NSObjects interchangeably with Swift objects - especially in dictionaries. - Annotating a protocol defining a weak var with

@objc.

Some compilation errors that caused some significant head scratching:

- A warning complaining of an inability to cast a subtype to its supertype when passing in a closure as an argument to a class implementing a protocol. This was caused by a missing

@escapingannotation in the protocol definition of the closure argument.

We would like to thank the team, Emily Toop, Farhan Patel, Stephan Leroux, Bryan Munar, Catalin Suciu, Simion Basca and Aaron Train for their contributions, diligence and dedication to seeing this through.